What is COPD? Causes, symptoms, treatment

Definition:

COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is a pulmonary disease that leads to a chronic obstruction of airflow from the lungs. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of pathophysiology, let’s nail down some key points to keep in mind as we go through this.

1. Limited Airflow

In COPD, airflow is restricted. Why? Because in the bronchioles and alveoli sacs, there’s chronic inflammation. This inflammation deforms and narrows the bronchioles. Adding to the problem, there’s excessive mucus production. This combination limits the amount of oxygen that can reach the alveoli for gas exchange and also hinders the expulsion of carbon dioxide.

2. Inability to Fully Exhale

Patients with COPD struggle to fully exhale. This is primarily due to the loss of elasticity in the alveolar sacs. Healthy alveoli are like nice, circular balloons that inflate and deflate uniformly. In COPD, they become floppy and lose their shape. This loss of elasticity disrupts proper gas exchange, throwing blood gases off balance and leading to the development of air pockets over time, especially in emphysema.

Important Reminders about COPD:

- Irreversible and Variable: COPD is irreversible and has no cure. The severity varies greatly from person to person. Some individuals might have a mild case, while others experience severe limitations, struggling to even speak a full sentence without breathlessness.

- Managed, Not Cured: COPD management focuses on lifestyle changes and medications. We’ll delve into medications and nursing interventions shortly.

- Environmental Causes: The most common cause is environmental, stemming from harmful irritants inhaled into the lungs over time. Smoking is a major culprit, with cigarette smoke constantly bombarding the lungs with damaging chemicals. However, non-smokers can also develop COPD due to severe air pollution or workplace irritant exposure (e.g., welders without proper masks).

- Gradual Onset: COPD typically develops gradually. People often start noticing symptoms in middle age, such as increasing shortness of breath during normal activities, chronic cough (sometimes productive, like “smoker’s cough”), and recurrent lung infections like pneumonia. Diagnosis usually follows a doctor’s examination and tests.

GOLD and mMRC CAT Classification

To further classify COPD severity and guide management, healthcare professionals use tools like the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) criteria and the mMRC (modified Medical Research Council) dyspnea scale, along with the CAT (COPD Assessment Test).

- GOLD Classification: This system assesses airflow limitation severity based on spirometry results (FEV1). It categorizes COPD into stages 1-4, from mild to very severe. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)

- mMRC Dyspnea Scale: This scale measures the patient’s level of breathlessness on a scale of 0-4, from “not troubled by breathlessness” to “too breathless to leave the house.” National Institutes of Health (NIH) – National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- CAT (COPD Assessment Test): This questionnaire assesses the impact of COPD on a patient’s daily life, considering symptoms like cough, sputum, chest tightness, breathlessness, activity limitations, confidence leaving home, sleeplessness, and energy levels. COPD Foundation

Types of COPD: Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema

COPD is an umbrella term for diseases that restrict airflow. In this post, we’ll focus on chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

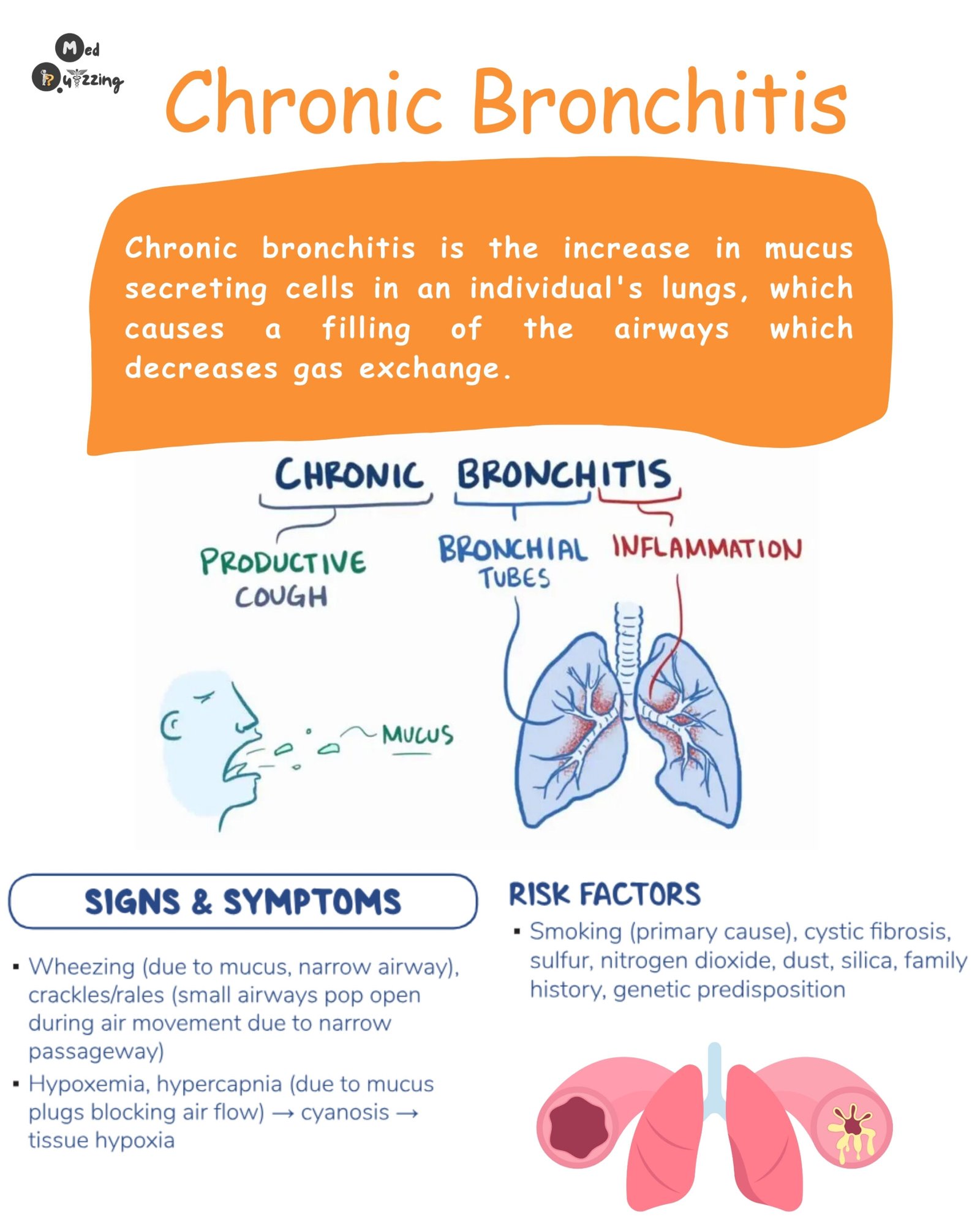

Chronic Bronchitis: The “Blue Bloater”

Patients with chronic bronchitis are sometimes called “blue bloaters.” This contrasts with emphysema patients, known as “pink puffers” (more on that later). The “blue bloater” moniker comes from cyanosis (bluish discoloration) due to hypoxemia (low blood oxygen). You might notice blue around their lips, mucous membranes, and skin. They also tend to have edema (swelling), particularly in the belly and legs. In severe cases, chronic bronchitis can lead to right-sided heart failure.

Pathophysiology of Chronic Bronchitis:

Let’s compare a healthy lung to one affected by COPD, specifically chronic bronchitis. In a healthy lung, oxygen flows smoothly through the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and into the alveoli sacs for gas exchange. The diaphragm contracts to create negative pressure for inhalation and relaxes for exhalation.

In chronic bronchitis, often caused by smoking or irritant inhalation, the bronchioles become inflamed and mucus-filled. This narrows the airways, obstructing oxygen from reaching the alveoli and hindering carbon dioxide removal. Patients struggle to fully exhale, leading to carbon dioxide retention.

With each breath, more air gets trapped, causing hyperinflation of the lungs. This enlargement flattens the diaphragm, further impairing breathing. Patients may then rely on accessory muscles to breathe.

Gas Exchange in Chronic Bronchitis:

The reduced oxygen intake and carbon dioxide retention lead to respiratory acidosis. Low oxygen levels cause cyanosis. The body tries to compensate by increasing red blood cell production to carry more oxygen, but this thickens the blood. This, in turn, increases pressure in the pulmonary arteries, leading to pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary hypertension forces blood back into the right side of the heart, potentially causing right-sided heart failure. This backflow affects the liver, causing hepatic vein congestion and fluid buildup in the abdomen and legs (“bloating”). It can even progress to left-sided heart failure.

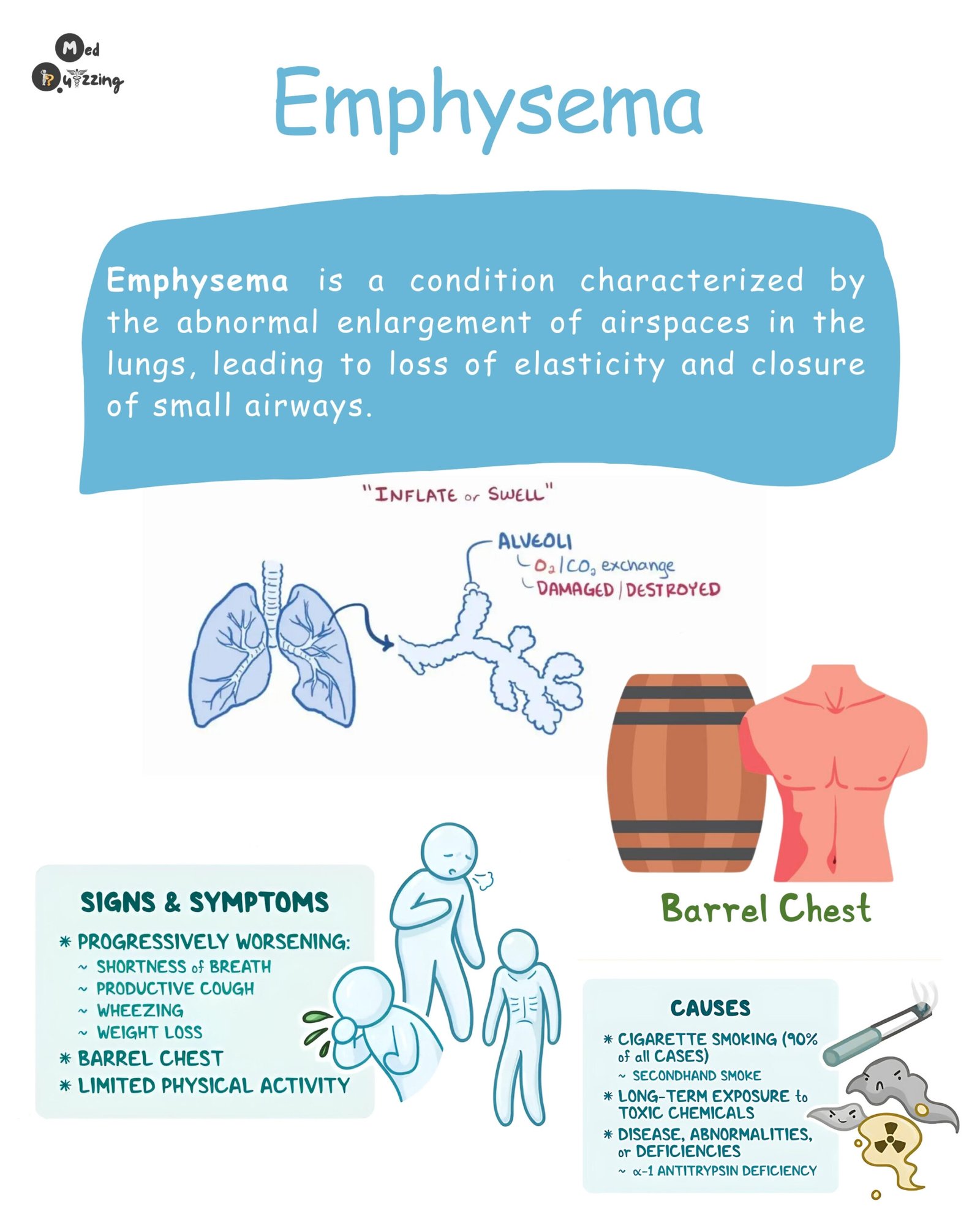

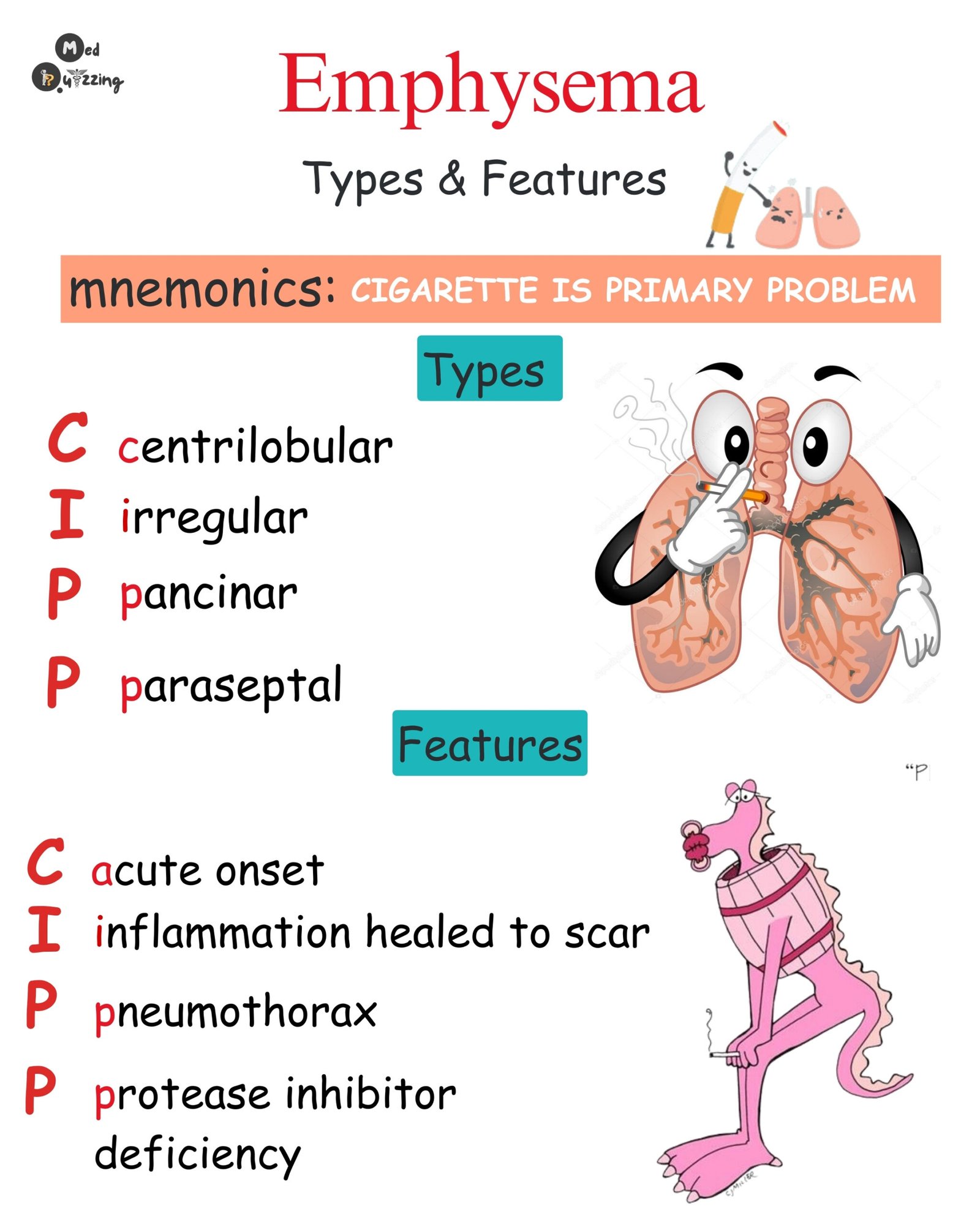

Emphysema: The “Pink Puffer”

Emphysema patients are often called “pink puffers.” Unlike “blue bloaters,” they typically don’t have cyanosis (hence, “pink”). The “puffer” part comes from their hyperventilation – rapid breathing to compensate for low oxygen levels.

Pathophysiology of Emphysema:

In emphysema, caused by irritants like smoke, inflammation triggers the release of substances that destroy the elasticity of the alveoli sacs. These sacs become deformed and lose their ability to inflate and deflate properly, severely impairing gas exchange. Carbon dioxide is trapped, and oxygen intake is reduced.

Similar to chronic bronchitis, the damaged alveoli don’t fully deflate, leading to air trapping and lung hyperinflation. The diaphragm flattens, and the body compensates by using accessory muscles in the chest to force air out and hyperventilating to increase oxygen intake. This overwork of accessory muscles contributes to the “barrel chest” appearance often seen in emphysema patients – an increased anterior-posterior chest diameter. The hyperventilation is the body’s attempt to maintain oxygen levels, hence the “pink” complexion despite the underlying issues.

Signs and Symptoms:

“LUNG DAMAGE” Mnemonic

To help you remember the signs and symptoms of COPD, think of the mnemonic “LUNG DAMAGE”:

- Lack of energy: Limited oxygen supply makes any activity tiring.

- Unable to tolerate activity: Shortness of breath even with mild exertion.

- Nutrition poor: Especially in emphysema. Patients burn extra calories breathing and eating can be exhausting.

- Gases abnormal: Arterial blood gases show high carbon dioxide (pCO2 > 45) and low oxygen (pO2 < 90), often indicating respiratory acidosis.

- Dry or productive cough: Chronic cough, often productive in chronic bronchitis due to increased mucus.

- Accessory muscle usage for breathing: Especially in emphysema, due to diaphragm flattening.

- Modification of skin color (cyanosis): Bluish skin, lips, mucous membranes, more common in chronic bronchitis.

- Anterior-posterior diameter increased (barrel chest): Mainly in emphysema, from accessory muscle use and hyperinflation.

- Gets in tripod position to breathe: Leaning forward with hands on knees to ease breathing during episodes of dyspnea.

- Extreme dyspnea: Significant shortness of breath.

Complications of COPD:

- Heart Disease/Heart Failure: Especially right-sided heart failure, linked to pulmonary hypertension (more common in chronic bronchitis).

- Pneumothorax (Collapsed Lung): Spontaneous lung collapse due to air sac formation, particularly in emphysema.

- Lung Infections (Pneumonia): Increased susceptibility to lung infections.

- Lung Cancer: Higher risk of developing lung cancer.

Diagnosis of COPD:

- Spirometry: The primary diagnostic test. Patients breathe into a tube to measure:

- Forced Vital Capacity (FVC): The total volume of air exhaled after a deep inhalation. A low FVC can indicate restrictive breathing.

- Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second (FEV1): The amount of air exhaled in the first second. A low FEV1 indicates the severity of airflow obstruction.

GOLD and mMRC CAT Classification

To further classify COPD severity and guide management, healthcare professionals use tools like the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) criteria and the mMRC (modified Medical Research Council) dyspnea scale, along with the CAT (COPD Assessment Test).

- GOLD Classification: This system assesses airflow limitation severity based on spirometry results (FEV1). It categorizes COPD into stages 1-4, from mild to very severe. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)

- mMRC Dyspnea Scale: This scale measures the patient’s level of breathlessness on a scale of 0-4, from “not troubled by breathlessness” to “too breathless to leave the house.” National Institutes of Health (NIH) – National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- CAT (COPD Assessment Test): This questionnaire assesses the impact of COPD on a patient’s daily life, considering symptoms like cough, sputum, chest tightness, breathlessness, activity limitations, confidence leaving home, sleeplessness, and energy levels. COPD Foundation

Monitoring:

- Lung Sounds: Regularly auscultate lung sounds to assess for changes (diminished, coarse crackles, wheezing).

- Suctioning: Be prepared for nasotracheal suction if needed, based on breathing effort and oxygen saturation levels.

- Sputum Production: Monitor sputum for changes in color, consistency, and amount. Chronic bronchitis patients often have productive coughs, and sputum cultures may be necessary to rule out pneumonia.

- Oxygen Saturation: Maintain oxygen saturation between 88% to 93%. This lower target is crucial for COPD patients because their breathing drive is stimulated by low oxygen levels, not high carbon dioxide like in healthy individuals. Excessive oxygen can suppress their respiratory drive, leading to hypoventilation and increased carbon dioxide retention.

- Oxygen Administration: Administer oxygen as prescribed, typically at 1-2 liters via nasal cannula, and closely monitor breathing effort.

- Breathing Techniques: Teach and reinforce pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing, especially during episodes of shortness of breath.

- Pursed-Lip Breathing: Instruct patients to inhale normally and exhale slowly through pursed lips (as if blowing out a candle). This technique helps to prolong exhalation, prevent airway collapse, and reduce air trapping, thus improving oxygen levels.

- Diaphragmatic Breathing: Teach patients to use their abdominal muscles for breathing, rather than accessory muscles. Have them lie down with knees bent, place one hand on the chest and the other on the abdomen. Instruct them to inhale deeply, feeling the abdomen rise while keeping the chest still, and then exhale slowly through pursed lips, engaging the abdominal muscles. This strengthens the diaphragm, reduces accessory muscle use, and conserves energy.

Treatment:

Medication Regimen for COPD: “Chronic Pulmonary Medications Save Lungs”

Mnemonic “Chronic Pulmonary Medications Save Lungs” (CPM SL):

- C – Corticosteroids:

- P – Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors:

- M – Methylxanthines:

- S – Short-acting Beta2 Agonists (SABA):

- L – Long-acting Beta2 Agonists (LABA):

- L – Long-acting Muscarinic Antagonists (LAMA) – Anticholinergics:

- Combination Inhalers: Many inhalers combine LABAs, LAMAs, and/or corticosteroids for convenience and improved adherence. Examples include:

- LABA/Corticosteroid: Symbicort (formoterol/budesonide), Advair (salmeterol/fluticasone)

- LABA/LAMA: Anoro Ellipta (umeclidinium/vilanterol), Combivent Respimat (ipratropium/albuterol – short-acting)

- LAMA/LABA/Corticosteroid (“Triple Therapy”): Trelegy Ellipta (fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol)